The Dolomites almost didn’t happen. They had been recommended to us, and our friends in Switzerland had unfortunately been laid up by injury, freeing time at the end of our trip through Europe. The alta vias or “high ways/routes” through the mountains were booked well in advance, and our first glance was not promising: accommodation in the rifugio mountain lodges of the most popular routes had booked out months ago. Incredibly, we glanced again, during a bus ride in Iceland at the end of the Laugavegur Trail, and there had very obviously been a large group cancellation on Alta Via 1, with the rooms already refilling. Nick hurriedly started booking us in, our dates and distances determined by what the group had left behind in their wake, and we were committed.

We had a wonderful few days with our friends in Switzerland, a broken foot not holding Laure back from mushroom and raspberry foraging. She and Pierre-Do had helped restore a mountain hut with their caving club, and we had the wonderful cabin to ourselves and our friends for the weekend. We explored caves with tiny glaciers inside them, and I managed to get briefly but quite genuinely lost in the karst landscape of gentle slopes, trees and the sound of cowbells – it was a very pastoral and picturesque place to be completely disoriented in.

Then it was off and up into the mountains of the Southern Limestone Alps, and the jagged mountain range previously known as the “Pale Mountains” before French minerologist Déodat de Dolomieu described the mineral by which we now know them: the Dolomites. Formed 250 million years ago by coral and shell deposits in the Triassic Tethys Sea, the force 30 million years ago from the European and African tectonic plates colliding made the seabed into mountains. They are famous as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, featuring “some of the most beautiful mountain landscapes anywhere, with vertical walls, sheer cliffs and a high density of narrow, deep and long valleys.” The mountains also have a fascinating human history, having been occupied since the Bronze Age and conquered multiple times, most famously when the Italians and Austro-Hungarians fought over them in World War 1. “Over them” doesn’t capture the scale of the conflict: the use of mining underneath and cableways between the mountains was extensive, including an entire city of 12kms of tunnels under the Marmolada Glacier, or under the Tofana Wall, where “four teams of 25 to 30 men worked in continuous six-hour shifts, drilling, blasting and hauling rock, extending the tunnel by 15 to 30 feet each day. It would eventually stretch more than 1,500 feet.” More soldiers were killed by rocks, exposure and avalanches than in fighting: incredibly, after heavy snowfalls in December of 1916, avalanches buried 10,000 Italian and Austrian troops over just two days, and climate change is contributing to the reemergence of corpses from the mountains.

After the madness of the war, the tunnels and via ferrata (iron paths) continued to be utilised, and were soon part of the tourism experience. The most famous route, Alta Via 1, showcases both World War infrastructure and natural beauty, and is easier and less technical than other routes, with no compulsory via ferrata. We generally followed the route, starting in the north at Lago di Braies and going south, though we added on an extra leg in order to get some more technical via ferrata, and it was one of the highlights of the trip.

Lago di Braies is claimed to be the most beautiful lake in the Dolomites, and while we didn’t have much data to work with, we suspect that it is true. Then it was up a little over 1.3kms, down a little under 1.3kms, but with 16kms horizontal we had at least moved onwards, to Pederü. The Dolomites are very much multilingual, with locals speaking German, Italian and the Ladin language native to the valleys, although the start of Alta Via 1 was very clearly German influenced: we were eating knödel and Nick could *just* communicate with his remaining high school German.

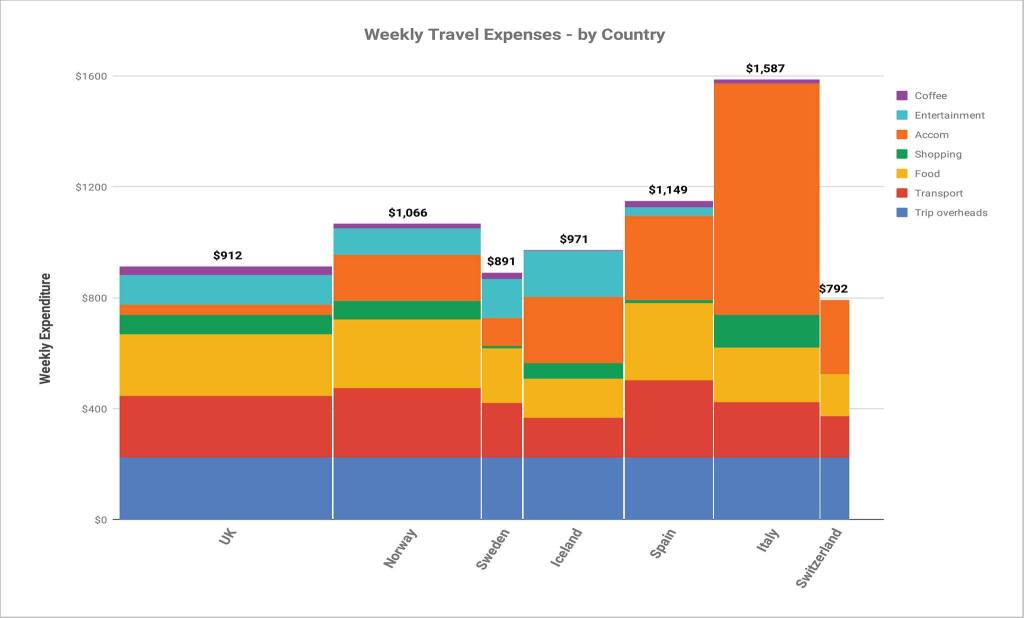

We were staying in rifugios, the mountain lodges that cater for walkers, as wild camping is strictly prohibited. It gave us the advantage of lighter packs, especially since we ate at the rifugios too, though it also resulted in Italy becoming the most expensive leg of our trip: in the famously expensive Norway we spent less than in Spain and Italy because, presumably being less tourism-dependent, they were accommodating of our wild camping and stove usage.

The next morning we headed to Lagazuoi, the highest and largest rifugio of Alta Via 1 (after nearly 2km vertical gain over 18kms), which also boasted an impressive vista, and along with Cinque Torri near the next night, hosted an open air war museum. Indeed, the next day we trekked down through more than a kilometre of tunnels that the Italians had dug under the Austrians, including “windows” out to the view… which were the soldiers way of assessing their location as they guesstimated their way upwards apparently. This, along with the non-compulsory section we did at Averau the night after Lagazuoi, were technically via ferrata, although the tunnels required little more than a headtorch and helmet, and we’ve definitely scrambled worse than the latter.

At this point our luck with the group cancellation that allowed us to do the Alta Via 1 had run out, and we interspersed the more typical rifugios (including the very well situated Tissi and Carestiato) with less common ones (Passo Staulanza) and even an agriturismo farm stay (Malga Pramper).

Nick’s timelapse of Tissi, below, includes the slackline that we got to ourselves all afternoon (made extra challenging by the cows nibbling it) and the climbers with their alpine start.

By day eight of Alta Via 1 we had reached Bianchet, after which most people finish. But a few days before the trip we had tacked on an additional night, in order to get some real via ferrata into the trip.

And that’s exactly what we got.

After feasting on wild blueberries, we had gear on, and with mist and drizzle intermittently concealing the mountains from us, we crossed the Schiara mountains. This was proper via ferrata, including some big drops over exposed edges, and bolts pulling out of the wall… and incredibly, Nick, supposedly afraid of heights, rated it as a highlight of the whole walk! We were quite sodden by our rifugio, 7 Alpini, but absolutely beaming.

To finish the trip, we even got both alpine and fire salamanders on the track.

It was an awesome trip (to everyone who recommended the Dolomites to us: yes, it turns out you were right!), and a perfect finish to our European travels. It also turned out to have been well-timed, since in half a year’s time, the world was about to enter a pandemic. By the end of the trip we were feeling the guilt of our carbon cost, and for a moment even thought that the pandemic might be a good chance for the world to accelerate decarbonisation, but the flying of literally empty planes over that period – while it relieved our personal sense of guilt – did nothing to alleviate the existential threat we face. At least our flights had achieved something – it is a trip that we will remember forever.

Great photos, fantastic videos, and kudos for the dedication to tracking expenses with such granularity!